Black movies more than just a color

April 5, 2017

Why do we still call movies by the race of their cast?

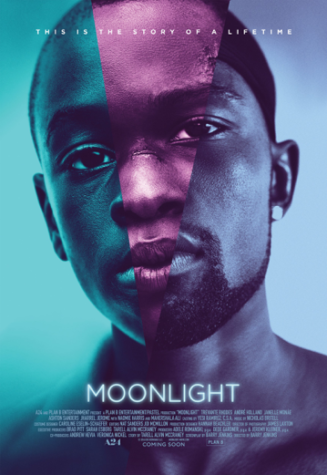

Moonlight won the 2017 Academy Award for Best Picture, receiving praise for its ambitious plot and superb acting among other accomplishments. It well deserved its eight Oscar nominations and three wins, and outclassed nearly every other movie nominated for Best Picture. Unfortunately, one adjective has the power to completely rewrite all of these achievements. This one adjective has the power to reclassify some of the greatest films and actors of all time into a category that calls them by their most basic attribute: the cast’s skin color.

When entered into Google, the search “black movies” yields millions of results, hundreds of movies, and dozens of ‘Top 10’ lists. In fact, Google even lists “black” as a movie category. In a 2005 Chicago Tribune article, African-American actor Terrence Howard describes black movies as, “any film that deals with the subject of black people, or has a predominantly black cast.” After all, every culture has its own uniqueness. While the definition itself is not inherently sinister or negative, the primary categorization of these movies can lead to unfair comparisons.

While it is very necessary to represent all cultures in film, their categorization as such should not be taken seriously. Films are always more than just the sum of their parts, no matter the genre.

Some films attempt to show the suppression that has historically and contemporarily plagued African-Americans and their culture. In the case of Moonlight, the plot follows a young gay black man as he comes to terms with his sexuality in an unsupportive environment. Although the Pew Research Center points out that LGBT acceptance is lower in black communities than others, support for gay rights is trending upward. A film like Moonlight at the right time could – and has – had a positive impact on the LGBT community.

As Howard mentioned, black movies can represent black culture in ways that music or art fail to. Seeing struggles portrayed in a very realistic way on the silver screen can illuminate serious issues to unaware audiences. Besides this, “black” culture has greatly expanded in the past 25 years, with traditionally African-American music and culture spreading to previously uninterested communities.

This too has its downsides. If a movie is unrealistic, it can spread misconceptions that may harm its subject material. This happened in the mid-to-late 20th century with the advent of blaxploitation films. These films were heavily based on stereotypes and untrue assumptions. Although these films can be viewed through a screen of satire nowadays, they severely discredited African-American actors and films as a whole, an impact which is still being felt today.

So what exactly is the problem with “black” movies? In short, the problem is that great films are being unfairly categorized by their shallowest characteristic. Yes, you can put a great movie and an objectively worse movie into the same category, but you’re missing the discrepancy in quality. These discrepancies can be seen in every category and genre of any aspect of culture, whether it be film, music, art, writing, or anything else.

The “black” label gathers films from a variety of genres which may not be very similar to each other. Often, the only common element doesn’t even affect the film as a whole. In this cultural day and age, racial labels and categories are completely outdated. Any film can be an Academy Award winner or a complete disaster, regardless of its cast.

The solution to this problem is simple: stop giving movies genres based on anything but the films content. In many ways, this is already the case. Most filmgoers identify movies by their major categories, such as comedy, drama, or action/adventure. Unfortunately, the genre of “black” movie continues to influence the public to this day.

Hopefully, viewers can disregard race when making their decisions at the box office, because there should be no such thing as a “black” movie in the age of equality.