The Danger of Desensitization: Global Events Through the Lens of Social Media

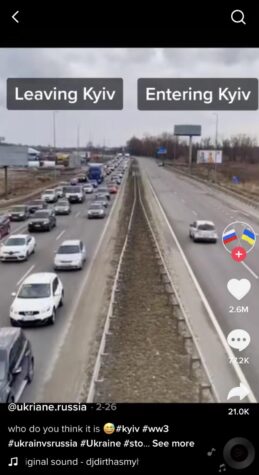

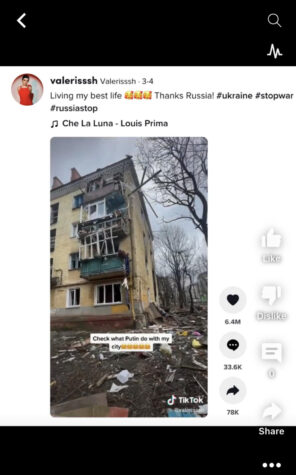

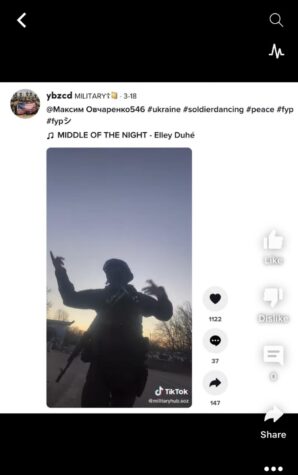

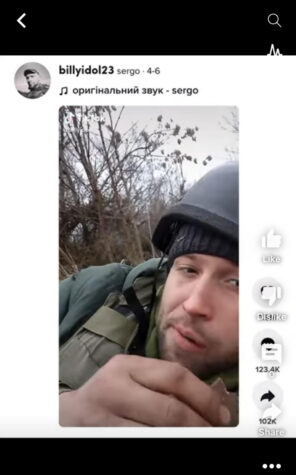

Ukrainian soldiers post a video of themselves doing a trending TikTok dance on the battlefield. Many people, even ones directly involved in the Ukrainian conflict, have been posting videos poking fun at the war leading to possible widespread desensitization. (Broadcaster/Screenshot)

Scrolling through TikTok, users see content tailored to their online identity. Some of the videos may be comedic skits, some may be how-to videos, some are about relationship advice. Endlessly swiping, an unassuming user can suddenly land on an intense video of missile strikes in Ukraine from a citizen point of view.

In the past, the public’s news consumption was limited to morning newspapers and evening television news programs. Yet now, in the age of Twitter, TikTok, and overall instant communication, opinions and false claims are very hard to avoid and very difficult to differentiate with real news.

Hershey High School Psychologist Dr. David Lillenstein said social media has been able to put news into people’s hands in near real-time. “You don’t have to wait,” said Lillenstein, “for the 6 o’clock or 11 o’clock news.”

It was not always like this. “We would get home after school and look at the paper to see what happened earlier in the day or the night before. There was always that delay,” Lillenstein said.

Immediate reactions to an event can be extremely different from a reaction to one later on. In the heat of the moment, emotions can and will overlap logic. People will quickly share their first thoughts, eager to be the first ones to have their opinions out there.

But Lillenstein doesn’t agree that this is the right first step. “Maybe find out some more information,” Lillenstein said, “verify, think, reflect, and then react.”

One of the problems with getting our current events from social media is figuring out if it is fact or fiction.

Hershey High School English Teacher Erin Ives said it can be dangerous when viewers do not get all of the information. “Social media itself has a strong presence of distorting factual information, “Ives said, “that’s part of the problem when you’re getting news in sound bites. That can really be discouraging to understand the complexity of the issues.”

The anonymity of an online persona gives a freedom not available offline. Anyone can say anything online, with consequences only as bad as a suspension or account deletion when creating another account takes just a few minutes. In this environment misinformation, disinformation and hate can flourish with few checks on its spread.

For example, Twitter’s maximum punishment for spreading a false or misleading post is deletion. Their policy states, “For high-severity violations of the policy including misleading media that have a serious risk of harm to individuals or communities, we will require you to remove this content.” After multiple infractions they may suspend or lock an account. Only for the very worst repeat offenders, will Twitter remove their account. But often the damage has been done by then. Ultimately, there is no way to fully avoid false news online.

Lillenstein agrees. “People [see] something on social media and then they have that immediate reaction, which is sort of the intent of social media,” he said. But if the information is false, and an immediate reaction to it spreads it further, then fake news gains traction. Online, one post or tweet can spread extremely fast.

With the growth of social media, a separate culture has bloomed as a result: meme culture. A meme, as defined by Merriam-Webster, is “an idea, behavior, style, or usage that spreads from person to person within a culture.”

This spread of ideas is most important here: memes get big fast, becoming some of the most well-known topics on the internet. With the addition of viral videos to this category, nothing can be taken completely seriously. Scrolling through a Tweet’s replies, reaction images and GIFs are interspersed with actual discussion.

Imagine a soldier shoots a video of Ukrainian troops walking through a ruined city. The soldier posts the video on social media with a certain intention, whether it be to show people a closer angle of war or even propaganda. The video then spreads to news outlets where they use it for whatever their agenda might be, even if it is opposite of the soldier’s intended use. It takes one more turn when someone on social media posts the same video, meant to be taken seriously, with funny music in the background. This combination of the video and music, as well as any text they include, could be referencing another meme or just making the situation more funny to naive users.

This situation is a hypothetical, however, similar scenarios happen almost daily all over the internet. The cycle of the video can be as fast as a few hours as different people get a hold of the content.

While some videos may contain facts, today’s internet culture leans towards heavily editing videos with trending “sounds,” or songs that are popular in the backgrounds of videos, to increase views. These videos, originally created to edit movies and TV shows, often include clips of current large-scale events such as the war in Ukraine, other countries’ reactions or opinions to these large-scale events, or even clips of people involved in the events, like Ukrainian soldiers, dancing to the songs during the war with full military equipment.

The problem with these videos, while they do raise awareness on the topic, is often romanticizing the war. Lillenstein said, “One of the problems with that, is it almost glamorizes it. It takes it out of the news realm and puts it almost into prime time TV.”

Glamorization sells on the internet and helps to promote a cause, but at the cost of risking the true human element of it. Too much glamorization causes observers to want more jarring content instead of actively trying to help in the situation. Lillenstein said, “It has the potential to desensitize people.”

Desensitization forms when online users constantly see graphic videos and begin viewing them as just another facet of social media. “They’re basically able to put the war in our hands,” said Lillenstein. As more graphic videos are being posted each day on different conflicts, they blend into normal parts of a Twitter or TikTok feed.

#frontline #Ukraine soldiers dancing to "keep the spirits up" among #UkraineCrisis #Russian tensions pic.twitter.com/LaZYJlpQ52

— Oliya Scootercaster 🛴 (@ScooterCasterNY) February 11, 2022

HHS English teacher Erin Ives has witnessed desensitization firsthand, especially with teenagers in school. “As teenagers, you don’t really understand the gravity of situations, and I think that that’s only amplified when social media is involved,” Ives said. “Social media has a tendency to trivialize the actual people who are at the core of what’s being inflicted upon them.”

Trivialization goes hand in hand with desensitization, Ives said. She said making certain aspects of a situation unimportant is dangerous, especially when it’s the emotional side that’s being compressed.

There comes a point when people are posting the graphic videos as entertainment, rather than information. Ives said, “I think that when people are looking for an angle to gain, popularity being current is the quickest avenue to do that. And unfortunately, [for] a lot of our social and civic issues, that currency can be used and manipulated to bolster the individual rather than the cause.”

Graphic videos are often used for views and to raise analytics instead of informing. When using such videos for likes rather than awareness, individuals prioritize themselves over the issues.

A document produced by TikTok’s engineering team in Beijing describes how the programming works. It also points out that the app “displays an endless stream of videos and, unlike the social media apps it is increasingly displacing, serves more as entertainment than as a connection.”

TikTok is currently one of the most used social media platforms by teens in the United States, according to Statista. The New York Times views it as a central vehicle for youth culture and online culture generally.

TikTok, specifically, uses an algorithm to determine what to show each user. The algorithm is the main reason for the massive popularity. It uses every kind of statistic from someone’s likes and comments to time spent watching each video.

The purpose is to keep people scrolling. Often this leads teens down a dangerous rabbit hole where they are unknowingly stuck cycling through content for hours at a time. This leaks into creators’ attempts to make news content. Even if they are genuine in their intentions to share content, they have also learned that social media is all about popularity and getting views.

When news videos and serious topics appear on someone’s TikTok feed but are interlaced with jokes or dancing videos, emotional reactions to each are extreme opposites. It can be very jarring to scroll through TikTok for entertainment or laughs and come across a triggering video. Once you see the dramatized videos, it is hard to not think that that is the way things are.

This is all happening while teens, the largest group of users on the platform, are increasingly using TikTok for entertainment.

Hershey Senior Sophia Brooks agrees the overhaul of intense information can cause people to become desensitized to genuine problems. Brooks attributes the COVID pandemic as the first example of how people became desensitized to a major world event. They recounted the beginning of the pandemic when they would hear about countless people dying every day, while also seeing jokes and memes about it on social media.

“I didn’t even process how bad it was before that because I see it all the time and everyone was making jokes about it,” Brooks said. “We all got desensitized to the idea of a pandemic.”

Brooks recalls the time before 2020 when they would hear about mass death and be much more surprised. However, now being able to see it constantly in real time brings a new feeling. The consistency of the people being affected, with case counts and death counts on the main pages of websites and social media sites, especially during COVID surges, was always readily available. Even now, extreme violence with the war in the Ukraine is always on the Twitter trending tab.

Brooks has done a large amount of research on the effects of social media because they want to know what exactly the negatives are and how it affects them. They think that this issue particularly can have a much larger impact on young people whose brains are still developing. They cite mood issues and perceptions of reality as possible main outcomes later in life. “You start to see this just surrounding of constant death and suffering and constant information as the only thing you’re accustomed to,” Brooks says. “You feel so connected to these other issues that it’s somehow both desensitizing, [and] it creates this feeling of helplessness.”

A study in the National Library of Medicine suggests that desensitization is linked to violent content. Seeing violence as a normal part of our daily social media check in and having it solidified in our subconscious as something that is always going to be on our feed causes it to feel normal.

Brooks said it takes the emotional impact away from the situation. We can logically acknowledge that the situation is awful, but we are stuck in a gray area where there is no form of grief or worry. The shock factor has disappeared, so there is barely a call to action. The significance of the issue becomes difficult to identify which makes it easier to ignore.

However, immediate reactions can be serious, according to Brooks. “A lot of people sensationalize things to make it seem scarier than it is, or undermine how scary it really is,” said Brooks, “and that can fuel so many anxieties and stressors that people can have just full-blown panic attacks over a global issue on the other side of the world.”

They said the sense of obligation to act after feeling these intense emotions. Even though the issues could be across the planet, it is hard not to want to help.

People may feel an obligation to still help in some way. However, according to Boston Medical Center, a type of activism called performative activism is extremely common. Performative activism occurs when people speak out on social media, often in the form of tweets or posts condemning hate such as racism or homophobia, but do not take any activism further. They only speak out to keep their social standing and to keep up a presence on social media.

Some may believe it helps, but they are not doing anything past solidarity, which does not make any progressive change, according to The Good Planet.

Brooks agrees, saying it is just a way to satisfy our feelings of helplessness. “The people who participate in it aren’t even doing it to separate the importance from what’s actually happening. They’re doing it to kind of hold their feeling of helplessness. Like how everyone changed their profile pictures to a picture of [the] Ukraine [flag].” It is almost like doing something small and logically useless will still be better than doing nothing in our minds.

While the majority of the conversations surrounding social media based news are unfriendly, it’s too early to tell for sure. Lillenstein believes that despite all of the negative impacts to come out of this issue, there could still be some good psychological effects.

“Maybe in the long run it will end up being better, that it creates a sense of urgency,” Lillenstein said. “Like, ‘oh my gosh, look at what’s going on, we got to do something about this now,’ as opposed to finding out about it three weeks later.”

Maeve Reiter is a senior and the Hershey Editor of the Broadcaster. She enjoys dancing and listening to music, and she is constantly carrying a book around.

Dan Hogan is the Science & Technology Editor in his third year with the Broadcaster. A senior, Dan enjoys baseball, movies, and nature.