39 Years Later, Effects of the Three Mile Island Accident Still Linger

February 27, 2018

Vietnam. Star Wars. Disco. Bell-bottoms.

These were all were enduring images of the 1970s, but for thousands of people living in Central Pennsylvania, nothing encompasses the decade more than three letters: TMI.

The 70s were a time of change in the United States. As the Vietnam War raged overseas, women in the US continued fighting for equality. The environmentalist movement took off in 1970 with the creation of Earth Day and persisted throughout the rest of the decade.

The decade also marked the start of the commercial nuclear power industry, with power plants being constructed throughout the country.

Nuclear power had been used in one way or another since 1942, when Italian Physicist Enrico Fermi created the first nuclear chain reaction. In 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which played a role in Japan’s surrender during the latter stages of World War II.

The United States developed a nuclear power program for its military in 1954, and by the 1970s nuclear power generating stations were popping up across the US.

The accident

In the early hours of Wednesday, March 28th, 1979, before the first rays of the early spring sun had crossed the banks of the Susquehanna River, the $400 million dollar Unit Two of Three Mile Island’s nuclear generating station, completed only three months earlier, experienced a minor malfunction.

The malfunction resulted in pressure building up inside the reactor’s cooling system, which prompted an automatic shutdown, according to the World Nuclear Association.

A loss of cooling caused severe damage to the reactor, and the situation was further magnified when the operators in the control room, due to a lack of training, were unable to diagnose the problem.

At 7:24 AM, a general emergency was declared.

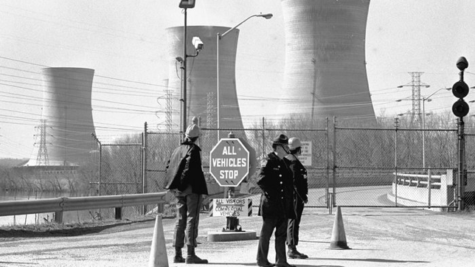

The Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency had minimal plans in place in the case of a nuclear meltdown.

“Out of about seven plans, it was number seven,” former PEMA director, Oran K. Henderson, said in 1989.

The tension reached its peak two days later on March 30, 1979, when a hydrogen bubble was discovered in the reactor. An explosion would cause the reactor core to be exposed and release massive amounts of radioactive material into the atmosphere.

That same day, Governor Dick Thornburgh ordered the evacuation of pregnant women and children within a five mile radius of the reactor. Many had already left. In total, about 144,000 people in the region packed their bags.

Eric Epstein was one of those residents that headed elsewhere. Epstein is the chairman of Three Mile Island Alert, an anti-nuclear group formed in 1977.

“A lot of people didn’t know if they were ever coming back,” Epstein says. “That is a psychic emotional experience that doesn’t heal.”

Epstein sums up the public reaction to the accident in one word: confusion.

“It’s hard to understand something you can’t see, feel, or taste,” said Epstein.

For the next two days, an entire region waited on edge.

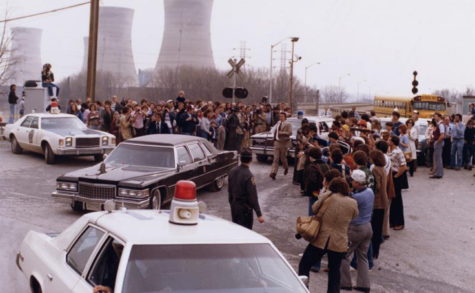

By then, the TMI saga had become a national news story. On April 1, 1979, then US President Jimmy Carter and his wife Rosalynn arrived in Middletown, Pennsylvania via helicopter to tour the plant. Carter, a former nuclear engineer himself, addressed residents in Middletown after the tour, assuring them that the reactor was stable. Two days later, Carter’s personal advisor, Harold Denton, announced that the hydrogen bubble had been eliminated.

The accident was over, but the recovery had just begun.

Ralph DeSantis was a security guard at the time of the accident. Mere months later, he would be thrust into the role of Three Mile Island’s Communications Manager.

“Shortly after the accident I took a job in communications, and it was my job to go out in the community and try to restore the public’s trust in TMI and its owner Met-Ed. Many people in the area felt like the company lied to them and we had to restore their faith in us,” said DeSantis.

Aftermath

Although a full meltdown was narrowly avoided, cleanup of the plant took 14 years, with costs estimated at $1 billion, according to the New York Times. TMI’s other generating station, Unit 1, was restarted in 1985.

For many years, there were believed to be no visible health effects from the accident. However, a recent study from the Penn State Medical Center found a link between the accident and thyroid cancer in south central Pennsylvania.

The New York Times ran a survey in 1977 to gauge public support of building more nuclear power plants. At the time, 69% of those polled felt strongly about the future of the industry. The same survey was run again in 1979, and public support dropped to 46%.

In 2016, public support of the nuclear industry fell once again in a Gallup poll in which only 44% of Americans were in favor of nuclear energy.

Interestingly enough, many of those living around TMI have found their fears of another accident fade over the past three decades.

“The fear comes from not having a plan when something happens, for what to do, where to go, what the sirens mean. Now we know,” said Middletown resident Deb Fulmer in a 2011 interview with the Washington Post.

Unlike Fulmer, others in the area have remained cautious.

Mary Osborn, who lives seven miles away from the plant, is an anti-nuclear activist. According to the same Post article, Osborn “tasted metal in the air the morning of the accident.”

Closing of TMI and future of nuclear power industry

After losing $800 million over the past five years, TMI’s owner, Exelon, recently announced its plans to shut down Three Mile Island forever in 2019. TMI’s Unit 1 will be dismantled and its radioactive fuel will be removed. The decommissioning process takes years, sometimes even decades to complete. With the closing of the plant, nearly 700 people will lose their jobs.

In some ways, the closing of the plant also brings to an end an entire era of nuclear power. In the immediate years following the accident, more than 120 orders for new reactors in the US were cancelled. The meltdowns in Chernobyl and Fukushima have only brought more negative attention to the safety and regulation of nuclear power plants.

Then, in March 2017, the nuclear industry experienced a major blow when Westinghouse Electric Company, one of the biggest names in the industry, filed for bankruptcy.

Ted Nordhaus of the Breakthrough Institute, a pro-nuclear environmentalist group, believes time is running short on nuclear power as a valuable resource. “The nuclear industry as we have known it is coming to an end,” Nordhaus said in a March 27, 2017 blog post.

Ralph DeSantis served as Three Mile Island’s communications manager for 38 years before retiring in February 2017. After originally taking a temporary security guard job, DeSantis ended up spending the majority of his life fighting to restore the public’s trust in the plant.

“I dedicated myself to nuclear power because I believe it is a vital energy source that is good for our environment and the future of our world,” DeSantis said. “The people who run nuclear power plants are extremely dedicated and professional, and I have always enjoyed working with them, in fact honored to represent them in the public.”

For DeSantis, Epstein, and countless others, the Three Mile Island accident has shaped lives and careers. While the future of the nuclear power industry lies in doubt, the events that unfolded in the spring of 1979 will never disappear from the minds of the people who worked and lived through them.