By Joel Neuschwander

Most people get excited when family or friends appreciate their cooking. For 13 years, John Moeller felt the same way: except at a far more prestigious level.

From 1992 to 2005, Moeller served the President of the United States and the First Lady as a White House chef.

Moeller’s extraordinary journey began in Lancaster, PA, where he grew up and started cooking at age 15. His first job in the kitchen was at Franklin and Marshall College, where he worked in the dish room and helped clean the kitchen. Once Moeller started to help the cooks in the kitchen, he realized he might consider a career in culinary arts.

Moeller went through tech training in the final two years of high school. He said the influence from his supportive parents pushed Moeller to be the best he could be. And then, Moeller said, “A lot like life, I was in the right place at the right time.”

After graduating from Lancaster Catholic High School in 1979, Moeller attended the culinary program at one of the top culinary schools in the country, Johnson and Wales University in Rhode Island. Being one of only two professional culinary schools at the time, and the other having a waiting list, led Moeller to attend. “Going to an accredited culinary school does help prepare you for what it will take to become an executive chef down the road.” he says.

That’s when it really took off.

Several years later, Moeller’s close friend, who was working in France at the time, told Moeller to join him. Moeller did, and for two years enjoyed the valuable experience of cooking in a foreign country.

Upon returning to the United States in 1987, Moeller met a group of French chefs in Washington, D.C. At the same time, the White House was searching for five chefs who could fill the kitchen: full time, and two pastry chefs. One of the french chefs, Pierre Chambrin, had formed a close relationship with Moeller. Chambrin was selected for one of the five spots, and was notified that the White House needed an American chef that had experience with cooking french cuisine. Chambrin asked Moeller to be his assistant. Moeller jumped at the opportunity, capitalizing on his experience of cooking in France.

Moeller joined the White House for the final six months of President George H.W. Bush’s term in 1992. Often working alone, it was his job to prepare meals for arguably the two most important people in the United States.

For Moeller, a typical day working at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue started off well before the sun rose. He needed to have a menu for the coming week prepared several weeks in advance. He also was required to have breakfast ready to be served by 6 A.M.. This meal had to be prepared and inspected by a butler who came into the kitchen to look for things to add. During the presidency of George W. Bush, Moeller notes that First Lady Laura Bush usually enjoyed steel-cut oats, and how both Laura and George normally ate fresh fruit as well.

Lunch was a little bit less of a rush, as the President and First Lady often ate separately due to their busy schedules. After lunch, the work day was finished for Moeller.

Moeller felt the pressure of cooking for the Commander-in-Chief; “You never forget it,” he said. Despite this pressure, the workload was often light, leaving Moeller with plenty of down time. Moeller used this as an opportunity to talk with America’s first family.

He said, “It was extraordinary to get to know the President and First Lady on a personal level. Politics had nothing to do with what we did.”

Moeller’s favorite moment at the White House might not have been shared with the President. Julia Child, a force in the food business in the 1960s and one of the first chefs to be featured in her own cooking show, paid a visit to the White House for lunch. She was so impressed with the cooking that she left a note thanking Moeller and the rest of the chefs.

One experience during his time at the White House Moeller would rather forget was on September 11, 2001. During one of the deadliest terrorist attacks in our country’s history, he and the other staff members were preparing for a big dinner on the White House lawn scheduled for that night. After the Twin Towers went down, they found out that they could be a target. Then they were ordered to evacuate. Luckily for Moeller, this was one of the only times the White House faced a threat in Moeller’s tenure.

In 2005, the landscape of the kitchen was constantly changing; one chef even left the White House Kitchen.That, combined with the pressure of writing menus in a short amount of time, led Moeller to believe he wanted a change of scenery. “I thought it was time to do something on my own,” Moeller said.

Five years later, tragedy struck when Moeller’s brother passed away at the age of 50.

After visiting family in Lancaster, Moeller decided that the city would be a perfect place to take on a new challenge: his own catering business. In his catering business, Moeller drove to push the envelope, using his experience to expand on the past and create new ideas, and always looking for more inspiration.

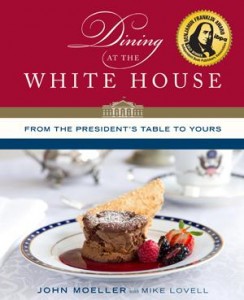

In 2013, Moeller shared his White House experiences and recipes in a book titled “Dining at the White House: From the President’s Table to Yours.”

One of Moeller’s favorite ideas, braising meats until they become tender, is one of his usual things to cook at home. Moeller describes this as “very soul-satisfying.”

Becoming a great chef starts with working the menial jobs in a kitchen. Moeller believes aspiring chefs should work on learning the many basics of their trade and gain experience by working at a quality establishment.

The first job in the kitchen is a low one, usually a line cook, before a chef can move up the ranks. As a line cook, many skills can be learned from the chef he/she works for.

Some chefs, like Moeller, will choose to attend culinary school after graduating high school. Culinary programs focus on in-class instruction and hands-on training in the kitchen. An alternative to that would be a formal apprenticeship program which combine hands-on training with classroom education. A small number of chefs learn how to cook through the military.

According to Amy McKeever on eater.com, the best known culinary schools in the country come with a hefty price tag-some ranging from $35,000 to $54,000 for a two-year associate’s degree or up to about $109,000 for a bachelor’s degree. McKeever is a proponent of culinary school, “One can have a reasonable expectation of emerging from culinary school with a foundational knowledge of terms used in the kitchen.”

According to Mckeever, is that a student can have access to university libraries and time to study. She believes it can also be beneficial to learn in a low-stress environment, as opposed to the fast pace of a restaurant kitchen. “What culinary school can give you,” Mckeever said, ‘is the knowledge that will make transitioning into a professional kitchen easier.”

Being a chef involves putting in long hours, physical labor, and heavy competition. Good time-management is also needed in the tense environment of the kitchen.

“Medium Raw: A Bloody Valentine to the World of Food and the People who Cook,” is a book written by a professional chef named Anthony Bourdain who expressed his strong opinion against the idea of culinary schools. “I’m not telling you that culinary school is a bad thing. It surely is not. I’m saying that you, reading this, right now, would probably be ill-advised to attend—and are, in all likelihood, unsuited for The Life in any case.” Bourdain said in his book. Bourdain also says if an amateur chef is still planning on attending culinary school, he recommends going to one of the top schools like Johnson and Wales, where Moeller had attended.

A roadblock for many chefs is the lack of money that would prevent them from the necessary training to improve their culinary skills. Bourdain estimates that a normal chef takes on about $40,000 to $60,0000 in debt in order to receive adequate training, all while only making $10 to $12 an hour. After graduating, the average chef will be up against the wall with debt.

Bourdain believes the best job after graduating for an amateur cook would be either at a hotel or country club. He said that they promise a “decent, relatively stable career if you do well.”

With chances unlikely that a major restaurant will select a chef straight out of culinary school, Bourdain recommended working for as long as possible in “the very best kitchens that will have you.” He also urged cooks to travel far to gain experience. This was the case with Moeller, who served valuable time cooking across America and in France. This led him to earn a coveted spot at the White House.

The point of view of the International Culinary Center is of stark contrast. On its website, it says that, while education is not strictly required to become a chef, it recommends going to culinary school. The website says that chefs who attend it will “gain a sense of focus and confidence with hands-on training in the kitchen covering safety, sanitation, baking, cooking techniques, food preparation and plating.”

The center also goes on to say that some culinary students earn a two-year associate’s degree or a four-year bachelor’s degree in culinary arts, while others receive a diploma from an intensely focused program that lasts six months.

Chef G. Stephen Jones believes some chefs do not realize how difficult it is to make a career out of cooking. In an article on reluctantgourmet.com, he said “Even people with no goals of stardom, who just wish to cook professionally, may lack an appreciation for the incredible amount of difficulty that lies ahead to even come within sight of, if ever, of such aspirations.”

Jones said, “You will do more than your share of ‘scut work’ first.” He is referring to putting in long hours for a low-end job in the kitchen.

Jones also went on to say that “experience is the biggest teacher,” meaning that culinary school would not be absolutely necessary.

There really is no prerequisite for getting into the restaurant business, says Chef David Chang. He suggests that there are many options, and culinary school is just one of those options. “It’s a relative free-for-all.” he says.

Jones notes that there are other culinary occupations: food stylists, caterers, and restaurant consultants, but says the hours are just as grueling.

As difficult as Jones believed it is to become a professional chef, it might become a bit easier in the near future. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) estimates that jobs for chefs and head cooks are expected to increase by five percent from 2012-2022. As of 2012, there are 115,400 jobs for chefs and head cooks in the U.S. Although there is a large turnover rate for this occupation, many restaurants have been trying to use cooks in place of chefs to save money. As of May 2013, the average annual salary for U.S. chefs and head cooks was $46,620.

‘Job opportunities should be best for chefs and head cooks with several years of work experience. The majority of job openings will result from the need to replace workers who leave the occupation. The fast pace, long hours, and high energy levels required for these jobs often lead to a high rate of turnover,” the BLS website said.

Throughout this long process, a young chef will be tested mentally and physically, and be pushed to their limits. It takes hard work and perseverance to reach the top of the mountain and recognized as a top chef. John Moeller was able to reach the top with a lot of skill and a little bit of luck.